The

Interior

and

the

Exterior

— Noah

Purifoy

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior — Noah Purifoy, 2015

Book published by Steidl — Pre-order

Excerpt from three-channel soundtrack

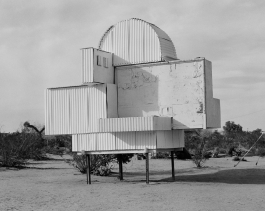

As a traveller from another history and a different continent, when I came across Noah Purifoy’s sculptures spread across the desert, I felt like an explorer encountering the ruins from another time and place. Noah Purifoy was born in a sharecropper family at Snow Hill, Alabama. After an engagement with the radical movements of California in the sixties, he moved to Joshua Tree in the Mohave desert where he spent his final years. After his death in 2004 these structures were preserved as monuments to his vision.

By recycling found materials he created visual references that stretched back to his childhood — the shacks, churches and graveyards of the South, the trains that went west, the segregated washrooms and buses, the yard-sales, and burnt down buildings left by the Watt’s rebellion. The monuments are sited to create a map of stark meanings. The detritus of technology is piled up and abandoned in contrast to the landscape of the surrounding desert. In places there are echoes of the imagined remains African rituals. As morning light rose some structures appeared to float. At mid-day the lack of shelter and the harshness of the scene heightened the polarity of black and white in the structures. When light fell the shacks appeared to dissolve into the distance.

It is inevitable when photographing such structures that Walker Evans’ earlier view of the American vernacular comes to the surface. Evans’ view of the South was that of an outsider. Purifoy’s vision was drawn from his life. Both come from periods of American history in transformation. The conclusion to Purifoy’s vision will be the return of these structures to the desert itself.

H.C.

The

Interior

and

the

Exterior

— Noah

Purifoy

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2015

All images are 50.8 x 61cm selenium toned black and white prints accompanied by three-channel soundtrack

The Interior and the Exterior — Noah Purifoy, 2015

Book published by Steidl — Pre-order

Excerpt from three-channel soundtrack

As a traveller from another history and a different continent, when I came across Noah Purifoy’s sculptures spread across the desert, I felt like an explorer encountering the ruins from another time and place. Noah Purifoy was born in a sharecropper family at Snow Hill, Alabama. After an engagement with the radical movements of California in the sixties, he moved to Joshua Tree in the Mohave desert where he spent his final years. After his death in 2004 these structures were preserved as monuments to his vision.

By recycling found materials he created visual references that stretched back to his childhood — the shacks, churches and graveyards of the South, the trains that went west, the segregated washrooms and buses, the yard-sales, and burnt down buildings left by the Watt’s rebellion. The monuments are sited to create a map of stark meanings. The detritus of technology is piled up and abandoned in contrast to the landscape of the surrounding desert. In places there are echoes of the imagined remains African rituals. As morning light rose some structures appeared to float. At mid-day the lack of shelter and the harshness of the scene heightened the polarity of black and white in the structures. When light fell the shacks appeared to dissolve into the distance.

It is inevitable when photographing such structures that Walker Evans’ earlier view of the American vernacular comes to the surface. Evans’ view of the South was that of an outsider. Purifoy’s vision was drawn from his life. Both come from periods of American history in transformation. The conclusion to Purifoy’s vision will be the return of these structures to the desert itself.

H.C.